African-American Education in the Jim Crow South

|

Top photo: 1948, Arkansaw Traveller. Photo by Ed Clark.

|

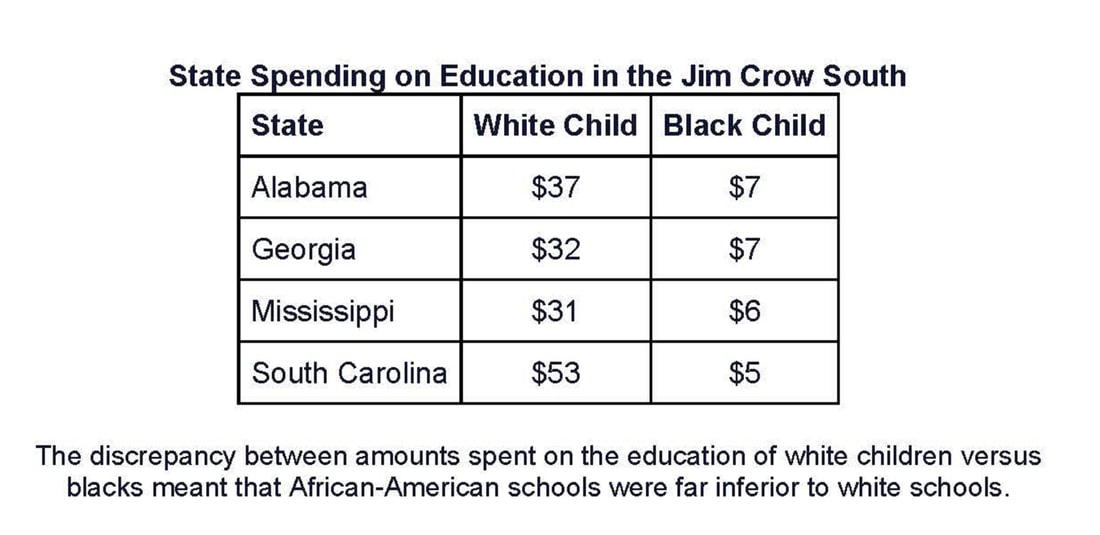

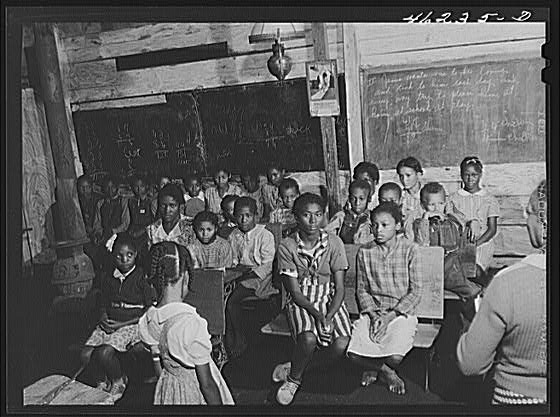

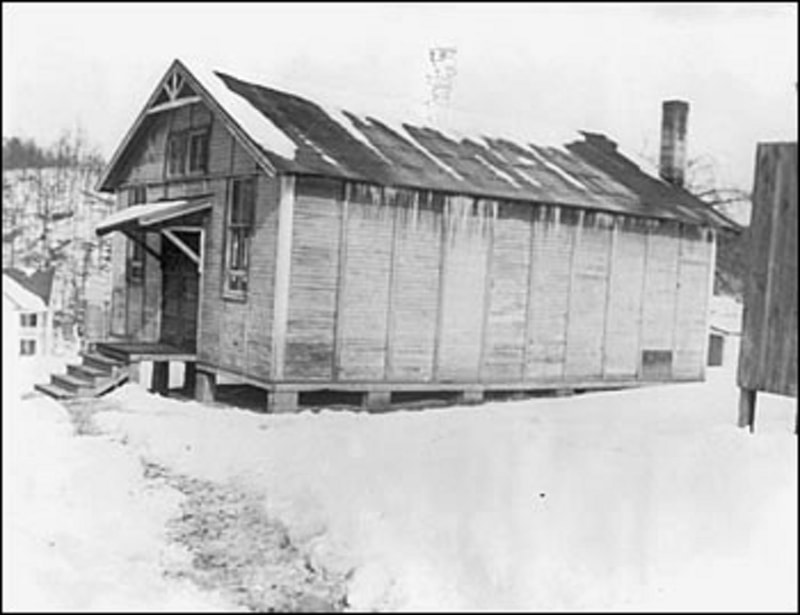

The schools for African-Americans in the South were separate but by no means equal, when they existed at all.

African-American schools were dilapidated and without supplies such as books, pencils, or desks. The teachers were untrained, and students were crowded together in inadequate space.

"A typical rural Negro school is at Dine Hollow. It is in a dilapidated building, once whitewashed, standing in a rocky field unfit for cultivation. Dust-covered weeds spread a carpet all around, except for an uneven, bare area on one side that looks like a ball field. Behind the school is a small building with a broken, sagging door. As we approach, a nervous, middle-aged woman comes to the door of the school. She greets us in a discouraged voice marked by a speech impediment. Escorted inside, we observe that the broken benches are crowded to three times their normal capacity. Only a few battered books are in sight, and we look in vain for maps or charts. We learn that four grades are assembled here." - Report of School Investigators, 1930s, in Irons [10] Only 20% of African-American children were enrolled in school compared with 60% of Whites.

Whites believed anything but a rudimentary education was wasted on African-Americans, and in fact might make them “unfit to work in white homes." [10]

This system of inferior education for African-Americans did not just happen. It was the logical outgrowth of a social ideology designed to adjust black southerners to racially qualified forms of political and economic subordination. [11]

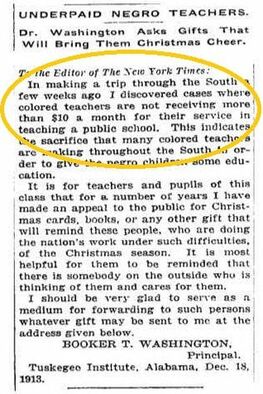

These Jim Crow schools were designed to teach students only those skills needed for domestic and agricultural work, to suit the needs of the white economy and society. [10] “I found that there was no provision made in the house used for school purposes for heating the building during the winter…with few exceptions, I found the teachers in these country schools to be miserably poor in preparation for their work, and poor in moral character. The schools were in session from 3 – 5 months.” - Washington, Up From Slavery [12] |

|

Two men, one an educator and the other a philanthropist, partnered to change the dreadful inequities of African-American education.

|